I am the first scholar of ghost towns, beginning my PhD research in Bodie, California in 1993. I am also a former ghost-town resident, having lived in one of Bodie’s abandoned cabins for ten summers while I worked maintenance for California State Parks. I now serve as the President of the Bodie Foundation, where we raise money to support stabilization and interpretation in Bodie, both of which are among my areas of expertise. I have published numerous journal articles, book chapters, and encyclopedia articles about ghost towns and Bodie, and most recently curated world records for ghost towns for the 2026 Guinness World Records.

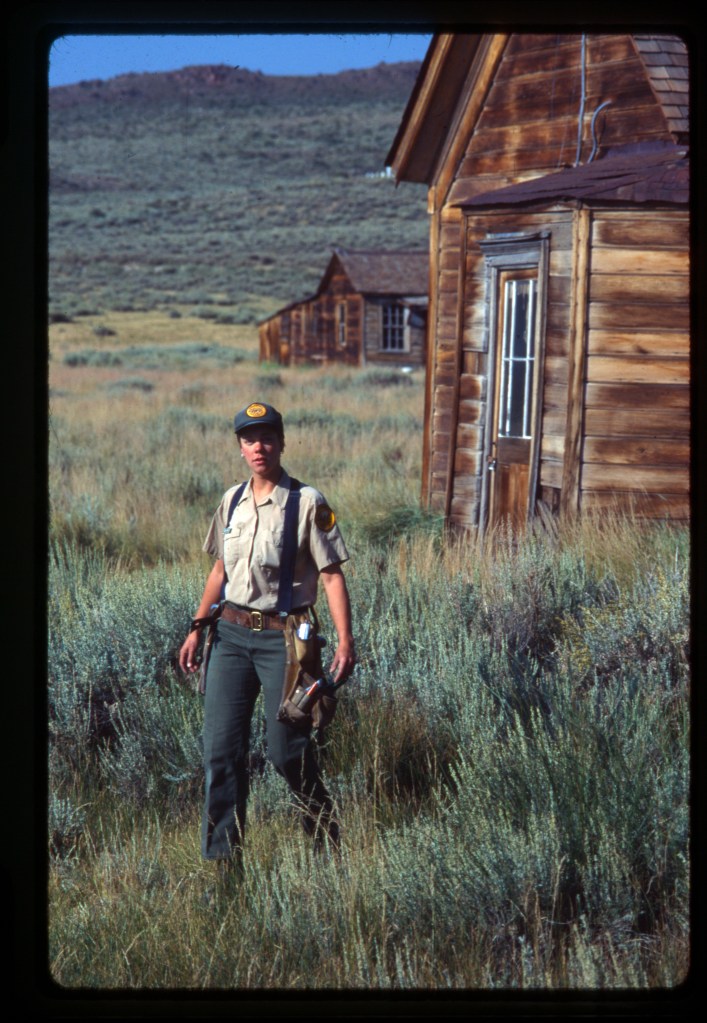

Dydia DeLyser working for California State Parks in Bodie, California in the late 1980s.

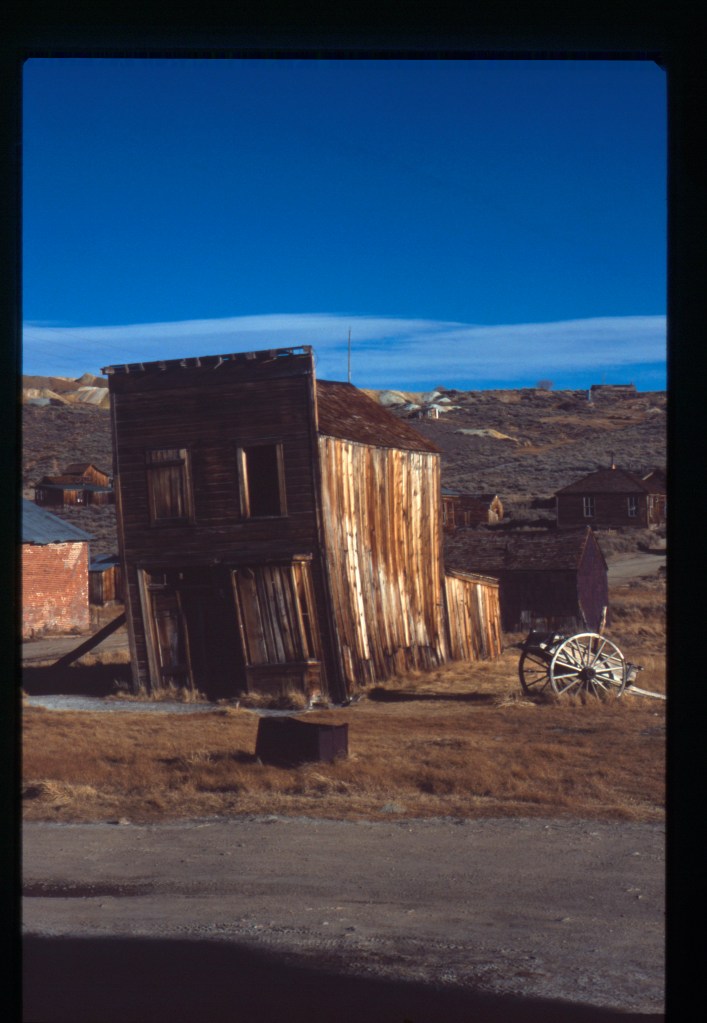

Photographs of Bodie on this page by Dydia DeLyser.

My research showed how visitors to ghost towns have powerful experiences, linking themselves, through details in the abandoned landscapes, to images of the American mythic West, familiar from film and fiction.

By the end of the 20th century many Americans had grown up watching (re-runs of) movie westerns like Stagecoach (1939), The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), High Plains Drifter (1973, filmed near Bodie) and Unforgiven (1992), as well as seeing western serials like Gunsmoke (1955-1975) and Bonanza (1959-1973) (also often in rerun) on the big screen or on TV—so much so that it was common for visitors to Bodie to whistle Sergio Leone’s evocative theme song from The Good, the Bad, and then Ugly as they explored the townsite.

The western genre—works of fiction (emerging in 19th-century dime novels, and expanding to novels, silent films (like The Great Train Robbery (1903), talkies, and television shows) took place across the American West in the time between the Gold Rush of 1849 and the 1880s when what was understood as the “American frontier” was thought to be “closing,” and the novels and other works romanticized the places, the period, and the people, just as they were perceived to be vanishing. They fashioned desolate landscapes of wide open spaces and dust-speck towns where gunslingers and gamblers drank and fought in the saloons, where white-hatted heroes never shot a man in the back, where prostitutes had a heart of gold—and these iconic scenes and characters helped to shape how Americans thought of their past and of themselves.

My research revealed—for the first time in rich ethnographic detail—the role that ghost towns played in cementing the mythic West as part of the American national imagination, and showed how visitors to a ghost town like Bodie used the ghost-town landscape to link themselves to the artifacts they recognized inside Bodie’s buildings, and from there to the heroic and upstanding pioneers of the mythic West.